Bombs over Brookings – Japanese attack Oregon in WWII

Published 11:10 am Saturday, September 9, 2017

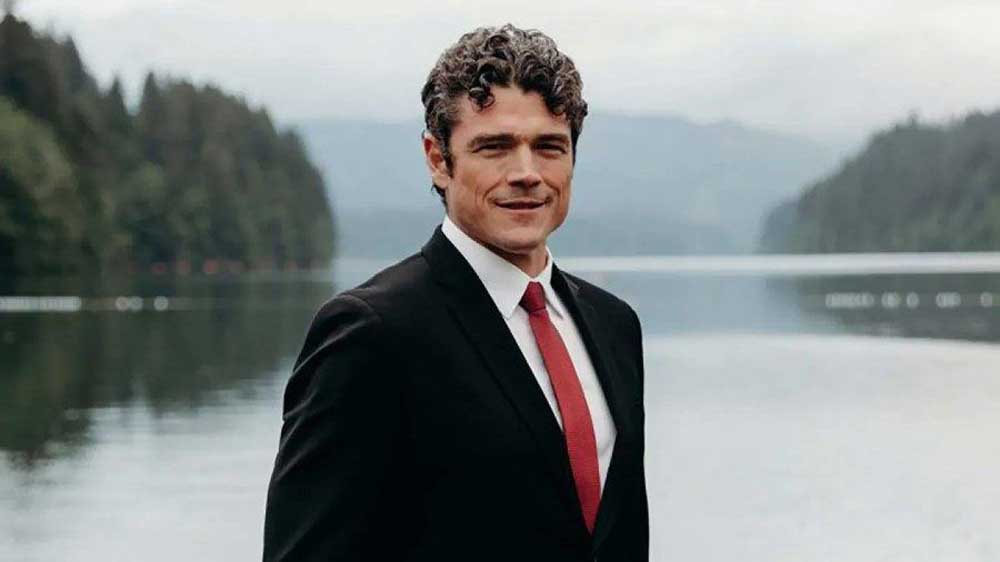

- Imperial Navy Flying Warrant Officer Nobuo Fujita, the pilot of an attack near Brookings in September 1942. It was the only bombing of the U.S. mainland in World War II.U.S. Navy

(First published Sept. 9, 2017)

The massive Chetco Bar “megafire” has burned more than 140,000 acres in its march toward the Pacific Ocean, heading straight for the town of Brookings in the far southwestern corner of Oregon.

Trending

In its path is one tree that is irreplaceable: a redwood sapling that marks the site of the only bombing of the United States in World War II.

Saturday is the 75th anniversary of the firebombing that couldn’t start a fire. Nobuo Fujita, a Japanese Navy pilot, dropped incendiary bombs on the forests near Brookings. All fizzled. Fujita would return to Brookings after the war to apologize for the attack. His family planted the redwood as a sign of reconciliation between onetime mortal enemies.

Now the Chetco Bar Fire threatens to destroy the redwood, along with the trail and monument built over the years by Oregon.

“The fire is a little over a mile away for that tree,” said Chris Papen, spokesman for the Emergency Command Center in Brookings. “We are working to hold the line on the west side. That’s where most of the homes are located. But this is a big fire.”

After the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor that brought the United States into World War II, Americans struck back with the “Doolittle Raid” in April 1942. Sixteen Army B-25 Mitchell bombers were launched from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet to bomb Tokyo and other Japanese cities. Damage was light and only 50 people were killed, but it showed the Japanese they were vulnerable to attack in their homes.

One of the bombs landed in the Yosokuna shipyard, near the submarine I-25. Among its crew was Fujita, a 30-year-old veteran pilot who had flown dangerous reconnaissance missions over Sydney, Australia, and Wellington, New Zealand. He presented his superiors with a plan: Bomb the United States using the I-25, a large “cruiser” submarine that carried a Yokosuka E14Y floatplane, a type nicknamed “Glen” by the Allies.

Trending

Much of the West Coast of the U.S. bristled with forts and Navy bases. The Glen had a cruising speed of 90 mph, making it a sitting duck for any American coastal battery or destroyer patrol.

The weak point was Oregon, whose sparse population and rocky coast left it relatively unprotected. What Oregon did have was forests — trees that were being turned into lumber to build hangars, barracks, ship decks, and ammunition crates. The idea was to drop thermite firebombs that would ignite massive wildfires, destroying millions of feet of war material and showing the Americans that they too were vulnerable in their homes.

In the early hours of Sept. 9, 1942, the I-25 surfaced off the coast of Crescent City, California. Fujita received a final briefing.

“You are going to make history today,” the submarine commander told Fujita. “You are going to show them who really owns the Pacific.”

Aided by a catapult, the plane was pushed into the pre-dawn sky, carrying two 168-pound bombs. Fujita later recalled the sun rising over the mountains and the rolling emerald green forests that stretched into the distance wherever he looked. He was enchanted, but not dissuaded from his mission. He dropped his bombs and turned back to sea.

As he had expected, the plane was widely seen, but there was no weapon that could reach even the sluggish floatplane as it headed west to rendezvous with the submarine. Unsure of the effect of the bombs, Fujita flew another mission days later to the same area. Upon his return, the submarine headed away from the U.S. and signaled Tokyo that the mission had been accomplished.

“INCENDIARY BOMB DROPPED ON OREGON STATE. FIRST AIR RAID ON MAINLAND AMERICA. BIG SHOCK TO AMERICANS,” trumpeted the headline in Tokyo’s Asahi Shimbun newspaper.

The report was half correct. Due to a malfunction or the wet Oregon weather, none of the bombs, on either mission, caused much of a fire. An alert U.S. Forest Service worker, seeing smoke, was able to put out flames from one bomb by himself.

But the raids did provoke alarm up and down the coast.

Fujita had fortune on his side throughout the dismal years of World War II.

Because he was assigned to the submarine plane, Fujita avoided the fate of hundreds of his pilot friends who died at Midway and other battles Japan lost. The decimated ranks led the Navy to reassign Fujita to a job training pilots, including kamikaze who were to crash their planes into American ships.

And soon after he departed the I-25, it was sunk off the southern tip of the Solomon Island with all 100 crew members killed.

The war over, Fujita returned to a Japan decimated by larger planes that dropped powerful firebombs on his homeland. He opened up a hardware store and along with the Japanese recovery made a new life for himself, and for two decades never talked about the war with his family — until the day he announced to his family that they were going to Oregon to visit the townspeople he had tried to kill.

It was 1962 when Fujita received an invitation from the Brookings Jaycees to visit the town on the 20th anniversary of his mission. The town wanted him to be the Grand Marshal of the annual Azalea Festival. Japan was now an ally in the Cold War and Tokyo would be the site of the 1964 Summer Olympics. City churches and service clubs had raised the $3,000 it would take to bring Fujita and his family to Oregon.

Fujita accepted, but was unsure of the reception he would receive. The Japanese government contacted the State Department to receive assurances that Fujita would not be arrested as a war criminal when he arrived.

He often told of his concern that he would be taunted and have eggs thrown at him.

But as an act of contrition and friendship, Fujita offered the most sincere apology he could think of: He surrendered his family’s 400-year-old samurai sword to city officials.

His daughter, Yoriku Asakura, told The New York Times in 1997 that Fujita’s fear and guilt was deep. If he was met with anger by the citizens of Oregon, he would commit seppuku — ritual suicide — using the sword.

“He wanted to take responsibility for what he had done,” Asakura said.

Instead, most in the town treated him with kindness, making sure he didn’t know about a full page ad taken out in the Brookings-Harbor Pilot opposing his visit, signed by 100 residents. The ad asked “Why Stop With Fujita? Why not assemble the ashes of Judas Iscariot, the corpse of Attila the Hun, a shovel full of dirt from the spot where Hitler died?”

Some newspaper reports at the time said the Forest Service worker who had put out the small fire caused by the bomb was so livid that the perpetrator of the attack was going to be honored that local authorities locked him in the jail for the duration of the visit. Two local teenagers ran a Japanese flag up a pole, but it was hauled down just before Fujita passed the spot.

Fujita gave the Brookings library $1,000 to buy English-language books about Japan. He financed the trip of three Brookings teenagers to Japan and offered to host any Brookings resident at his home for visits. In 1995, he visited Brookings for the last time as his sword was installed in a special exhibit in the new city library.

In 1997, Fujita was hospitalized with terminal lung cancer. The city of Brookings proclaimed him an honorary citizen and ambassador of international goodwill.

He died Oct. 2, 1997, at age 85.

In the Japanese Shinto religion, warriors who fought for the emperor are forever honored in the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, a controversial site where militarists and nationalists often rally in a show of “bushido,” the warrior code of honor. Fujita showed bushido in 1942, but his family did not believe his soul was destined for a militarist shrine.

Instead, his daughter brought some of his ashes to a spot on Mount Emily and sprinkled them around the bombing site. She told her father’s that his soul would forever be flying over the forests of Oregon.