Biography of Mark Hatfield highlights early years.

Published 1:01 pm Thursday, June 30, 2022

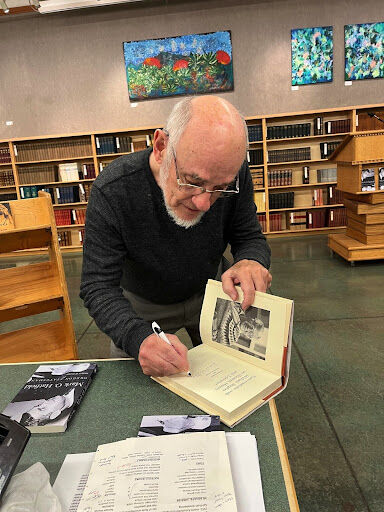

- Richard W. Etulain, a resident of Clackamas, signs one of his books during a recent appearance at Powell’s City of Books in Portland. Etulain’s latest book is “Mark O. Hatfield: Oregon Statesman.”

Had Richard Etulain graduated four years after he entered Northwest Nazarene College, he would have heard a 36-year-old Mark Hatfield speak at the commencement ceremony in May 1959.

But Etulain took an extra year to obtain a bachelor’s degree from what is now a university in Nampa, Idaho. He was pursuing an Oregon dairyman’s daughter who would later become his wife. So he did not hear Hatfield, then and now the youngest person ever elected governor of Oregon.

Trending

That changed during his six years in graduate work at the University of Oregon, where Etulain earned a master’s in American literature in 1962 and a doctorate in American literature and history in 1966. He was able to vote for Hatfield’s reelection as governor in 1962 and Hatfield’s nomination for U.S. senator in the 1996 Republican primary. But he left Oregon before Hatfield won the first of five terms in the Senate that fall.

Etulain, now 83, calls himself a lifelong Democrat.

“But I fell in love with Mark Hatfield’s style,” he said. “I saw him as a person who could work across the aisle.”

Etulain and his wife, Joyce, a retired children’s librarian, live in Clackamas. His academic career took him back to his alma mater, then Idaho State University, and the University of New Mexico, where he directed the Center for the American West. He is the author or editor of more than 60 books, including Abraham Lincoln and Civil War politics in the Northwest, and William S. U’Ren, father of the Oregon System of the initiative, referendum and recall.

Etulain also is the author of “Mark O. Hatfield: Oregon Statesman,” the first biography since the former Oregon governor and senator died in 2011 at the age of 89. It was published in 2021, but the impending centennial of Hatfield’s birth gives it more import.

The book focuses on Hatfield’s early years and the governorship — Hatfield was the first Oregon governor in the 20th century to serve two full terms, from 1959 until he became a senator in 1967 — but only summarizes (in 30 pages) his 30 years in the Senate.

Trending

Etulain said Hatfield’s Senate papers, which are housed in the library that bears his name at Willamette University in Salem, are scheduled to be open to researchers on the 100th anniversary of Hatfield’s birth on July 12.

Etulain does not gloss over Hatfield’s failings, but says his is “a sympathetic biography.”

“Even after I make allowance for his mistakes and where I disagree with his conclusions, I think him a role model for politicians,” he wrote in the preface.

Though Hatfield wrote a book a decade before his death — “Against the Grain: Confessions of a Rebel Republican,” published in 2001 — he also said he felt he was not the best judge of his place in history.

Other than his 93-year-old widow, Antoinette, most of those in Hatfield’s early political circle have died. The most recent on March 13 was Gerry Frank of Salem, the one-time department store owner who led Hatfield’s 1966 Senate campaign and was his Senate chief of staff and special assistant from 1967 to 1992. Frank was 98.

Humble beginnings

Hatfield, an only child, was born July 12, 1922, in the mid-Willamette Valley town of Dallas. His father, Charles Dolen Hatfield, was a blacksmith and railroad employee, a Methodist and a Democrat. His mother, Dovie Odom, was a teacher — she got her teaching credential from Oregon State University — a Baptist and a Republican. The family moved to Salem in 1931.

Though Hatfield never lost an election for public office in four decades, from his first bid for the Oregon House in 1950 until his final victory for the U.S. Senate in 1990, Etulain notes that Hatfield lost tries for student body president in high school and Willamette University.

His Navy service in World War II covered the seaborne invasions of Iwo Jima and Okinawa, and a visit to Hiroshima after the 1945 atomic explosion destroyed the Japanese city. His ship also stopped in Haiphong, then part of French Indochina, in what figured into Hatfield’s later opposition to U.S. military participation in the Vietnam War.

Hatfield identified early with Republicans. His master’s thesis at Stanford University was about Herbert Hoover’s relations with labor before Hoover became president. After Hatfield became a political science instructor at Willamette University and was elected to the Oregon House, he was an early supporter of Dwight Eisenhower for president in 1952. He was a delegate to the 1952 convention where Eisenhower prevailed over Robert Taft, who was favored by party stalwarts.

Etulain said that in contrast with his later years in public life, Hatfield began his political career as a relatively conventional Republican in support of limited government, focused on state and local instead of federal efforts, and better stewardship of the public’s money.

“But Mark Hatfield was more interested than most Republicans in helping people socially,” Etulain said.

Hatfield led the House committee that passed Oregon’s first civil rights law in 1953, a decade before Congress passed a national law to bar discrimination in public accommodations such as restaurants, theaters and lodging.

He won an Oregon Senate seat in 1954 and secretary of state in 1956. Two years later, he beat state Treasurer Sig Unander for the Republican nomination and then unseated Democratic incumbent Robert Holmes. At age 36, Hatfield remains the youngest Oregon governor ever elected.

Etulain said Hatfield’s youthful appearance — and his marriage that summer to Antoinette Kuzmanich — also helped his political fortunes.

Two-term governor

Unlike his successor as governor — Tom McCall would utter the words, “For heaven’s sake, don’t move here to live” — Etulain said Hatfield was a big economic cheerleader for Oregon during his two terms. Yet it was Hatfield, not McCall, who coined the term “livability” to describe Oregon’s attractiveness.

Hatfield sought to reorganize state government, reduce the number of agencies, rewrite the 1857 Constitution and revise the tax system — all of which Etulain said Hatfield largely failed to achieve. Though a coalition controlled the Senate, Democrats were the majority party in the House three of four legislative cycles — and in two of them were led by Robert Duncan of Medford, who was House speaker before he won a congressional seat in 1962.

Hatfield made some progress toward his goal in his final session in 1965, after a young lawmaker named Bob Packwood helped Republicans win a majority in the House despite the Democratic presidential landslide in 1964.

Hatfield also had to share power with the secretary of state and state treasurer, who together sat as the Board of Control to oversee state institutions other than higher education. (The board was abolished in 1969.)

But Hatfield’s frequent travels through Oregon, his support of business and tourism, and his rising national prominence — he was the keynoter at the 1964 Republican National Convention, balancing moderate and conservative — gave him a pathway to an open U.S. Senate seat in 1966, when Democrat Maurine Neuberger decided against reelection.

His opposition to increasing U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War was still a minority position in 1966, when Democrat Duncan, who supported the war, took him on. Hatfield did tie the war to negative consequences for the Oregon economy — and Hatfield prevailed, 52% to 48%.

Etulain said that in Hatfield’s eight statewide victories dating back to 1956, when registered Democrats outnumbered Republicans for the first time in Oregon history, “he had to win over Democrats to be continually victorious.”

Hatfield’s 30-year Senate career is still a record for Oregon, though Democrat Ron Wyden is likely to break it if Wyden is elected to a fifth full term Nov. 8 (Wyden has already served 27 years, on top of 15 years in the House.) Etulain said he had intended to cover those years, but that will have to await future historians.

Two scandals

Though Hatfield is remembered for his principled opposition to the Vietnam War, the buildup of nuclear weapons and a constitutional requirement for a balanced federal budget, Etulain does describe a couple of ethics controversies involving Hatfield, tarnishing his public image as “St. Mark.”

In 1984, Antoinette Hatfield accepted $55,000 from Basil Tsakos, a Greek businessman, for her help in obtaining and redecorating an apartment in Washington, D.C.

Tsakos was an advocate for a trans-Africa oil pipeline that Hatfield supported. The Hatfields donated the money to Oregon Health & Science University, and the Senate Ethics Committee concluded there was no evidence the Hatfields accepted Tsakos’ payments as bribes.

That same year, Hatfield won his fourth term by 2-to-1 over a Democratic challenger.

In 1991, after Hatfield won his fifth and final Senate term by a 54% majority over Democrat Harry Lonsdale, there were disclosures about Hatfield being the recipient of gifts (porcelain, Steuben glassware and an Audubon print) worth $9,300, plane tickets and a four-year scholarship for son Charles (Visko) from James Holderman, president of the University of South Carolina, who was seeking a $16.3 million federal grant for an engineering building. Other accusations involved favorable treatment for his daughter Elizabeth by Oregon Health & Science University, where Hatfield had steered millions in grants, and a partially forgiven loan from John Dellenback, a former U.S. representative from Oregon who urged Hatfield to support legislation benefiting a Christian college organization Dellenback worked for.

The Senate Ethics Committee did issue a formal rebuke in 1992. “My mistakes were many, and my omissions were serious,” Hatfield said at the time. “There is no one but myself to blame.”

Etulain said those two episodes, seven years apart, explain why Antoinette Hatfield set 2022 as the date for the opening of her husband’s Senate archives. Mark Hatfield is silent about them in his 2001 book.

“I think she did not want that information to come out” and subjecting her to relive those long-ago controversies, he said.

The centennial of Mark Hatfield’s birth will be observed in special events by the Oregon Historical Society.

One event is scheduled from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. Tuesday, July 12, at the society, 1200 S.W. Park Ave., Portland. Two of Hatfield’s successors as governor, Democrats Barbara Roberts (1991-95) and Ted Kulongoski (2003-11) will be among those sharing their memories, and root beer floats — a Hatfield favorite — will be served.

The traveling exhibit, “The Call of Public Service: The Life and Legacy of Mark O. Hatfield,” also will be on display at the event.

The second event is the move of the exhibit to the Mark O. Hatfield Research Center at Oregon Health & Science University, 3251 S.W. Sam Jackson Park Road, Portland, for a showing between Aug. 1 and Oct. 2. As chairman and ranking member of the Senate Appropriations Committee, Hatfield steered millions in federal grants to OHSU.

— Peter Wong