Tributes to Mark Hatfield on his centennial

Published 1:41 pm Thursday, July 14, 2022

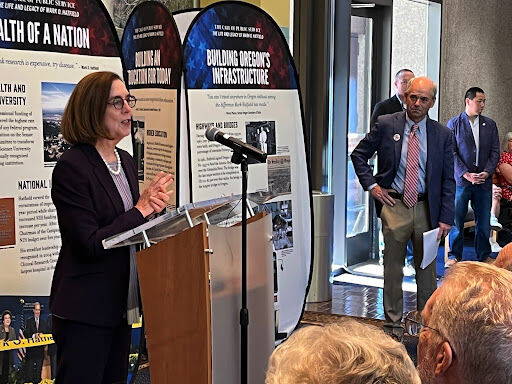

- Gov. Kate Brown speaks at the centennial celebration for Mark Hatfield on Tuesday, July 12, at the Oregon Historical Society in Portland as Kerry Tymchuk, OHS executive director, looks on (right).

Three of his successors as Oregon governor, two men whose institutions benefited from his work as a U.S. senator and afterward, and his youngest son all spoke at a centennial celebration of Mark Hatfield, whose 46 years in public office included eight years as governor and 30 years in the Senate.

More than 100 people attended the celebration Tuesday, July 12, at the Oregon Historical Society in Portland. Hatfield was born 100 years ago in the mid-Willamette Valley town of Dallas; he died Aug. 7, 2011, in Portland at age 89.

Trending

In addition to Charles “Visko” Hatfield, the youngest of four children, other family members in attendance were daughter Theresa and son-in-law Greg Keller, who was married 37 years to Dr. Elizabeth Hatfield Keller. She died Sept. 13, 2021, of multiple cancers. Mark O. Hatfield Jr. was absent; he is chief security officer at Miami-Dade International Airport, where he has worked since 2016 after 14 years at the federal Transportation Security Administration.

Hatfield’s wife of 53 years, Antoinette Kuzmanich Hatfield, survives him at age 93. She also was absent from the celebration, though she makes occasional public appearances.

Hatfield was governor from 1959 to 1967 — he remains the youngest person ever elected to that office — and a U.S. senator from 1967 to 1997. His Senate tenure, a record for Oregon, will soon be eclipsed by Ron Wyden, who has been a senator for more than 26 years and is up for re-election to a fifth full term Nov. 8.

The governors, all Democrats, focused on Hatfield’s public record and personal qualities. Two other speakers represented Portland State University — Hatfield raised money for the school of government named after him in 2000 — and Oregon Health & Science University, which benefited from an estimated $300 million in federal grants that Hatfield steered to it while a senior member and chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee.

“Visko” Hatfield’s message was much darker. He said his father would have been appalled at the current state of Oregon — particularly Portland, where Hatfield spent most of his years after leaving the Senate — and its sharply divided politics. Hatfield was a Republican, but he won eight times statewide going back to the mid-1950s, after registered Democrats began to outnumber Republicans in Oregon.

Kerry Tymchuk, Oregon Historical Society executive director and a one-time intern for Hatfield, closed with Hatfield’s comments in Hatfield’s final public appearance at the Oregon Capitol in Salem on Jan. 8, 2007. The occasion was the swearing-in of another former Hatfield intern, Jeff Merkley, as speaker of the Oregon House. Merkley won Hatfield’s former Senate seat in 2008.

Trending

Hatfield said:

“Years from now, Oregonians will not remember how many members of the House of Representatives were Republicans or Democrats. What they will remember is whether or not they were men and women of goodwill, whether they were Oregonians first — and politicians and partisans second.”

Excerpts from their comments are below:

Gov. Kate Brown:

“Senator Mark Hatfield’s impact on this state has always been a defining factor in what makes Oregon, Oregon. His example is perhaps more important now than ever. He was a bridge builder, not a bomb thrower. He formed working relationships and friendships across partisan lines. He was gracious in disagreement, and comfortable with nuance. He opposed the Vietnam War when it was not politically expedient to do so. He put principle above politics, breaking with his party on plenty of consequential votes.

“He set the example for Oregon that by working together, we can remain stewards and protectors of our environment while supporting our agricultural and timber industries. His example would set the standard for what has come to be known as the Oregon Way — the commitment to working together through differing perspectives and conflicting interests, in the service of building a better state for all who call Oregon home. And he made this a better state.”

Former Gov. Barbara Roberts, 1991-95:

She described two instances when as governor herself, she called on Hatfield for advice.

One was an unidentified death penalty case, which did not reach the stage where Roberts was faced with a public choice of commuting the sentence or letting the execution stand. Hatfield as governor in 1962 let stand the execution of Leroy Sanford McGauthey, convicted of the murders of a mother and child, though he opposed the death penalty. (Hatfield said years later he might have decided it differently. After voters repealed the death penalty in 1964, he commuted the sentences of the three inmates on death row, including a woman.)

“My duty and my conscience were in direct conflict. He felt my pain — and I felt his heart and his wisdom.”

The other was internal opposition within the Oregon National Guard to her appointee as adjutant general, in defiance of the governor’s authority as commander in chief. Roberts said she turned to Hatfield, who was not only a former governor but a World War II Navy veteran with combat experience in the Pacific.

Roberts left Oregon upon her high school graduation and marriage in 1954 — her then-husband was in military service — and returned in 1960 when Hatfield was governor.

“I never dreamed that one day I would hold that same office,” she said. “The day would come when I would turn to Senator Hatfield for help and advice. Today we remember the many facets of this remarkable man.”

Former Gov. Ted Kulongoski, 2003-11:

“That other side of the coin is what I remember most about Senator Hatfield. He believed in those values of honor, duty, respect, loyalty, patriotism, tolerance, religion — and above all, his oath.

“He understood that standing up for what is the right thing to do is not always easy or comfortable.

“I believe Senator Hatfield’s lasting legacy will be his personal values: His leadership, his courage, and his dignity as a representative of the people of Oregon. Character does matter. Senator Hatfield’s tangible accomplishments will stand the test of time. But his legacy will be the quality of the person he was — a kind and caring human being.”

Dr. Danny Jacobs, president of Oregon Health & Science University since 2018:

{img:339488}Jacobs referred to a Hatfield quotation in an exhibit directly behind him: “If you think research is expensive, try disease.”

“OHSU would not be the university it is today without Senator Hatfield’s commitment to public health. we believe Senator Hatfield learned from his experiences in the Navy, and later in political science and government studies, that human health and well-being are essential to democracy.

“Having witnessed firsthand the effects of hunger and poverty, he simply believed one could not have a stable and effective government if citizens were sick and infirm. No doubt, these observations influenced and focused his efforts and probably impacted the lives of people in Oregon.”

Buildings bear Hatfield’s name at OHSU and the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., where he spent several months before returning to die in Oregon. Hatfield also was on the OHSU board for several years, and was its chairman, after he left the Senate.

Max Wedding, graduate, Hatfield School of Government:

Wedding, who just graduated with a master’s degree in public administration from the Hatfield School of Government at Portland State University, spoke about some of the other students enrolled in the school.

“Today, we live, work and learn in a different world than the one where Senator Hatfield served, yet in many ways it’s very much the same world, with many of the same tensions, the same issues, the same systems and structures. But the senator’s values seem more relevant than ever as guideposts for students at the Hatfield School of Government.

“They showcase the importance of supporting those who are the most vulnerable in our community, bringing people together to work through our differences, and protecting the natural resources on which we all depend.

“His legacy also serves to reminds us of a shared responsibility — a responsibility to shepherd in a world where whatever spheres of influence are left behind, where these values are infused into the solutions we build and the systems we rebuild, and the policies we hope will shift us away from our violent present into a kinder future.”

Charles Vincent “Visko” Hatfield, his youngest child, born in 1965:

He decried the physical and social deterioration of Portland — much of it within blocks of the federal courthouse that bears his father’s name and opened in 1997 — and the political polarization of Oregon. “I’m not sure my father would recognize this great state of Oregon today.”

Oregon is full of people with many talents, he said. “Each of these Oregonians deserve better than the repeated partisan bickering and the failed policies of self-interested politicians who have wholly abdicated their responsibility of leadership and service in the name of destructive and cheap political theater.

“The average person is nearing the breaking point.”

He said there is still time for Oregon to change course.

“Stop fighting each other and start working with each other,” he said. “Step up, Oregon. Be the first to make a pledge to make a change.”

He said it begins with reconstituting a political middle ground.

“That is where discourse can be shared, compromise can be celebrated, it is what the average Oregonian expects. Let us continue and build upon an honorable legacy of service in the name of Oregonians and the great state of Oregon — and to share it with the rest of the country.”

Scholars and researchers will have access to Mark Hatfield’s archives compiled during his half century of public service in Oregon, as well as oral histories conducted after he left public office.

The Oregon Historical Society and Willamette University announced the openings on Tuesday, July 12, on the centennial of Hatfield’s birth. The former Oregon governor and U.S. senator died in 2011 at the age of 89.

A few oral history interviews conducted for the historical society had been available via the historical society’s digital history web page. None was with Hatfield himself. But Executive Director Kerry Tymchuk, a one-time intern for Hatfield, said the society has now released more than 30 hours of interviews with Hatfield conducted between 1998 and 2002. Interviews with others also were released.

An annual lecture series, bearing Hatfield’s name, has been sponsored by the society since 1998. The latest season is scheduled to start Oct. 18 at Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall with historian Doris Kearns Goodwin; other lectures will follow in 2023. The lectures in 2020 and 2021 were done via video link; subscribers had in-person or video options this past year.

Willamette University also used the centennial to announce the opening of Hatfield’s papers, which are housed in the library that bears his name on the Salem campus. The papers were under family control until Tuesday. A large room on the second floor displays many of the books Hatfield collected, heavy on U.S. history and presidents.

Hatfield was born in the mid-Willamette Valley town of Dallas and grew up in Salem. He earned a bachelor’s degree at Willamette University before U.S. Navy service during World War II. After one year of law school at Willamette — he dropped out — and a master’s degree from Stanford University, Hatfield returned to Willamette in 1949 to teach political science, He was first elected to the Oregon House in 1950, and to the Oregon Senate in 1954, but continued to teach at Willamette, where he become dean of men. He left Willamette in 1956 in his successful run for Oregon secretary of state.

He taught at Willamette briefly after he left the U.S. Senate in 1997, though most of his post-Senate academic career was in institutions closer to Portland, notably George Fox University in Newberg. Others were Portland State University, whose school of government bears Hatfield’s name, and Oregon Health & Science University.

“Willamette treasures the history and relationship with Senator Hatfield. We are proud to have his political papers,” said Sean O’Holleran, a former Hatfield aide and retired Nike executive, who leads Willamette’s current board of trustees.

O’Holleran should know. As a staff assistant to Hatfield in Hatfield’s later years, he had the task of helping Hatfield and others sort documents and other materials — even a rocking chair and a tribal headdress — that had been stored in the attic of a Senate office building. O’Holleran said it was no small task, given that Hatfield served 30 years.

“The senator loved books,” he said. “He loved history. He loved teaching. He loved being a professor. He loved government. And he loved being a husband and father.”