Farmers of color organize in Portland to overcome barriers

Published 1:56 pm Thursday, February 10, 2022

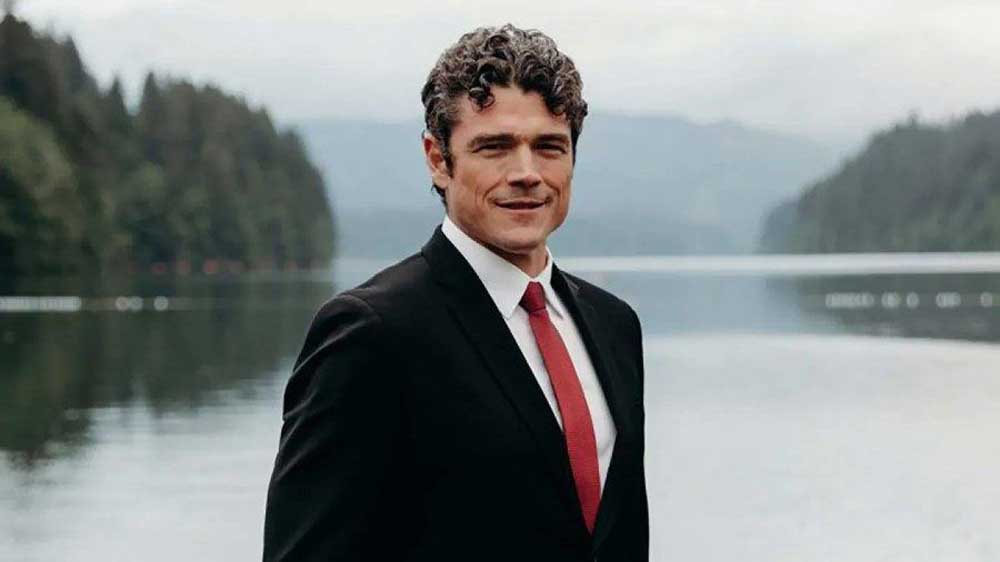

- Japhety Ngabireyimana, of Happiness Family Farm, talks with attendees of the Black and Brown Farmer Networking Fair on Sunday, Feb. 6.

Running a small farm is difficult for anyone.

But small-scale farmers of color in the Portland metro area face a particular set of barriers to sustaining the environmentally friendly, community-focused food businesses they strive for, says Surabhi Mahajan, a farm manager at Zenger Farm in Southeast Portland.

Trending

That’s why a group of Portland area farmers of color is organizing to build an ongoing network of support both amongst themselves and within the wider community.

On Saturday and Sunday, Mahajan and a couple of her colleagues from other local farms hosted a networking fair at the Southeast Portland food cart pod Collective Oregon Eateries to connect local Black and brown farmers to potential buyers.

The event included live music, educational materials about culturally specific farming and about 20 farmers of color, who set up booths with information about their products and farms.

More than 200 people attended the event’s first day, Mahajan said, and halfway through the second day, more than 100 people had stopped by to meet local farmers of color. Attendees consisted of food buyers from restaurants and community organizations, as well as individuals looking to source their produce.

“To be a farmer in this country is hard, and to be a sustainable farmer that’s successful is hard,” Mahajan said. “There’s not a lot of incentives to be a farmer. It’s physically hard on your body, and there’s not a lot of returns on investment for the products you grow.”

Only about 6% of agricultural producers in Oregon are Black, Indigenous and people of color, according to a report produced in 2020 using data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s 2017 Census of Agriculture. That proportion doesn’t capture farms under 10 acres, called “micro farms,” a category Mahajan said many of the farms at the networking fair fall into.

Trending

While there’s a lot of demand in the Portland area for locally grown, sustainable, fresh food, many farmers of color have missed out on the benefits of that demand, Mahajan says.

She said farmers of color face challenges with people’s implicit biases influencing their purchasing choices at farmer’s markets, one of the main ways small farmers sell their products.

Grants, loans and other resources from the USDA are typically reserved for large farms, Mahajan said. Additionally, decades of racially discriminatory practices by the agency have been well-documented.

Those barriers are on top of historical policies and practices, including Oregon’s Black exclusion laws and the relocation of Native American tribes, that dispossessed people of their land.

“A lot of people of color have been disconnected from their food source,” Mahajan said, adding that sourcing already scarce farmland is one of the biggest barriers to people of color starting and growing farms. “To get back into farming, or to get back into growing your own food, it’s a big resource-intensive act.”

Japhety Ngabireyimana, who set up a table at the networking fair and leads marketing efforts for his family’s farm, Happiness Family Farm, said obtaining land was a major barrier for his parents to start the business.

He said when his family moved to the Portland area in 2007 from a refugee camp in Tanzania, his parents started working low-wage jobs. But it was always their vision to support the family through farming, as they had in East Africa.

“Food is such a big connection to culture and family,” Ngabireyimana said, adding that his family farms many herbs and vegetables used in East Africa. “A lot of people come here from other countries and they want products they know from back home.”

Ngabireyimana’s family got help starting out from organizers with the Village Gardens, an organization that currently provides more than 80 garden plots in North Portland. After growing food at one of the organization’s community gardens, partners helped Ngabireyimana’s parents find a couple of acres of farmland on Sauvie Island and later a couple more in Vancouver.

His family is currently looking for new farmland to expand and be more efficient with a single growing location, a process he says is proving difficult.

He said he’s glad local farmers of color came together for the networking fair because it helps share knowledge with other farmers and reach new customers.

Ngabireyimana said Happiness Family Farms recently started offering a community-supported agriculture (CSA) program. Such programs allow people to pay a farm a lump sum for farm products, usually packaged bi-weekly or monthly, throughout the growing season.

Mahajan says connecting farmers of color with new potential CSA buyers was a main motivation for the networking fair.

Not only are CSAs are a key way for small farmers to have reliable income, she said, but they also help farmers give back to their communities and work to fight food insecurity. If farmers can count on CSA revenue, they don’t have to rely so heavily on bringing products to farmer’s markets, where oftentimes they end up throwing away some food they don’t sell, Mahajan said.

“Our goal is to have farmers sell out of their products during the season so they can accomplish their community goals,” she said. “A lot of people give things away to Black and brown communities so they can have better access to fresh produce, flowers, fruits, herbs, medicine. They can only do that if they have the financial resources available.”

Spencer Suffling, one of the networking fair’s organizers and a farmer at Tanager Farm in Corbett, said partners plan to continue hosting events like the fair in the future to strengthen connections between farms and build a consistent customer base.

He said farmers of color saw a boost in support and revenue shortly after the murder of George Floyd amid heightened awareness of racial and social injustices. But many farmers of color say that support has waned more recently, Suffling said.

“A lot of people come in and they say, ‘We need to support local agriculture, we need to support farmers of color,’ but then they don’t actually center the farmer in that conversation,” Suffling said. “It ends up being one-off things.”

Jeannine Shinoda came to the event to see if she could find farms to source produce for Ikoi no Kai, a community lunch program she works for through the Japanese Ancestral Society of Portland.

She said the program, which serves about 700 meals per month mostly to seniors, hasn’t previously sought to source produce in such a pointed way.

“I’m really just super happy they put this together and made it easy to think about how to consolidate and network,” Shinoda said. “There are a couple of farmers here that I think align with what we want, and we want to support them.”

For more information about the farms that participated in the networking fair and how to support local farmers of color, email Mahajan at sitafalfarm@gmail.com. People can also follow the local Black Food Sovereignty Coalition.