COVID-19 three years later: What’s happened, what’s next

Published 2:30 pm Friday, December 30, 2022

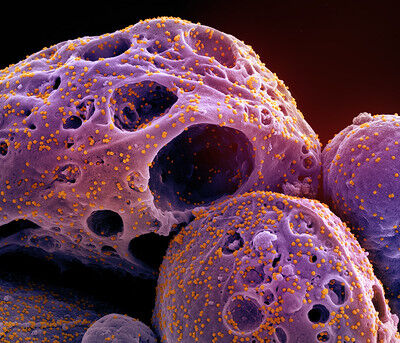

- The omicron variant attacks human cells in this microscopic photograph taken inside an infected person.

COVID-19 rings in another New Year this week, ever-present even as the world wishes for it to be in the past.

The pandemic announced on Dec. 31, 2019 has lasted over 1,000 days, sickened 100 million and killed more than 1 million Americans. The nation’s citizens have seen their life expectancy drop from 80 to just over 76 years because of the sharp upturn in death and serious illness since 2020.

But 2022 held some hope. COVID-19 spent most of the year stuck in an “omicron rut,” spinning off subvariants that spread faster, but with no significant increase in virulence of individual cases.

Dr. Peter Graven, lead forecaster on the pandemic for Oregon Health & Science University, issued his last 2022 forecast on Dec. 16.

“Oregon has seen peaks in emergency room visits from COVID-19 on Nov. 20, positive COVID-19 tests on Dec. 4 and levels of COVID in wastewater on Dec. 7,” Graven wrote.

Oregon has struggled with a “tripledemic” that also includes high numbers of flu cases and respiratory syncytial virus, known as RSV, which has a troublingly high incidence in children.

COVID-19 hospitalizations that topped 1,200 in August 2021 had topped out at 400 in the most recent upswing. Graven projected they would decline to under 200 by mid-January 2023 and continue to drop into spring.

Though hopeful numbers, it once would have been pessimistic in the extreme to think the COVID-19 crisis would still be going on two presidents, three Super Bowls and seven Marvel universe superhero movies later.

From eradication to endemic

The novel coronavirus appeared in Wuhan, China on the last day of 2019. It spread to Washington State by January and Oregon by February. While its spread was fearsome, there was hope that it would follow the path of other viral outbreaks and swiftly if violently burn through parts of the world before disappearing into the history books.

Stamping out COVID-19 was still the hope when through an astounding scientific effort, effective COVID-19 vaccines were created less than a year after the virus appeared.

But an uneven distribution worldwide, along with an unexpectedly large population in the United States who resisted voluntary inoculation, stalled progress.

Still, in early 2021 there were still 240 of the 3,143 counties in the United States reporting no cases. In November 2021, the virus was reported to have reached Kalawao in Hawaii, the last county to report an infection.

Americans integrated dozens of new words and terms in their vocabularies — asymptomatic, variant, congregant, virtual, Zoom, incubation, anti-vaxxer, incubation, oximeter, epidemiologist, monoclonal and oropharyngeal swabs.

Residents were told to avoid “superspreader” events like indoor concerts or packed rodeos by practicing “social distancing,” to “flatten the curve” of viral growth.

Endless acronyms roll past our eyes in the media and our ears in public service announcements: RNA, PPE, PPP, WHO, MERS, SARS, RO The difference between a N95 and a KN95 mask. Pronouncements came from WHO, OHSU, OHA, CDC, IHME.

The omicron variant that took hold by early 2022 was different from the deadly delta variant that preceded it. It spread faster than any variant before, but individual infections — especially among the vaccinated — led to far fewer severe cases and deaths. But it also showed an ability to get around the vaccinations and cause infections, requiring a rethinking of how to deal with the virus. Instead of eradication, scientists talked about the virus becoming “endemic,” where COVID-19 could linger for years but become manageable through public health programs, much like the seasonal flu.

As 2022 came to a close, Oregon has reported nearly 940,000 cases and 8,962 deaths. The state has had one of the lowest per capita infection and death rates throughout the pandemic.

China’s new policy puts world on alert

While omicron variants have shown to have less lethal outcomes in individual cases, the sheer volume of people hit by the hyper-contagious subvariants have led to packed hospitals in parts of the United States and the world.

The 2023 New Year comes with new worries. China had taken a “zero COVID” approach, using its rigidly controlled society to lock down swaths of millions of citizens, even in major cities like Shanghai. Social unrest boiled over, the economy was crippled by shuttered factories and choked ports. China’s currency, the yuan, was projected to lose 8.6% of its value, the biggest drop in 28 years.

In early December, Beijing reversed policy and lifted all major restrictions. Cases and deaths have reportedly skyrocketed, though world health officials say getting accurate figures from the country was impossible.

The specter of a nation of 1.5 billion people throwing off new virus variants with the contagiousness of omicron and deadliness of delta gripped officials from Japan to India, Europe to the United States. As before, new variants showed the ability to move from India or China, South Africa or Brazil and arrive in western Europe or the United States in weeks, sometimes days.

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, a leading pandemic forecaster, projected more than 323,000 fatalities in China by April 1. Airfinity, a British health analytics firm, told Reuters news agency that its models projected 1.7 million within the next four months could die in China.

The United States announced a requirement of a negative COVID-19 test from every passenger arriving on a flight that originated in China, regardless of nationality or vaccination status.

China’s chief epidemiologist Wu Zunyou responded on Thursday, telling Reuters that the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention is monitoring fatalities by measuring “excess deaths,” the number of people expected to die during any given period above what would be expected without the pandemic. How often and how thorough the reports will be issued wasn’t clear.

Anything close to the scenarios would swiftly add to the more than three years of COVID carnage, which has caused 700 million cases around the world since late 2019 and nearly 6.7 million deaths.

The good news of 2022 was that the formerly rapid roll call of variants — alpha, beta, delta, omicron — had slowed to just subvariants of the latter. If our daily common use of a letter of the Greek alphabet stops with omicron, then a long-term endemic virus that acts much like seasonal flu would be a difficult but more tolerable outcome for society.

But if next time this year, we know about upsilon and tau or omega, then the pandemic may not only be part of the past, but a more dominant part of the future.

Variants

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention uses viral genomic surveillance to quickly identify and track COVID-19 variants, and acts upon these findings to best protect the public’s health. Some variants spread more easily and quickly than others, which may lead to more cases of COVID-19.

Scientists monitor all variants but may classify certain ones as:

Variants Being Monitored – No risk to public health; Circulating at very low levels in the United States.

Variants of Interest – Potential impact on spread, severity, testing, treatment, and vaccinations; Evidence it has caused an increased proportion of cases or unique outbreak clusters.

Variants of Concern – Evidence of impact on spread, severity, testing, treatment, and vaccination. These have included delta and omicron.

There is a fourth level, one that has not yet been reached by COVID-19. It is the nightmare scenario for epidemiologists.

Variants of High Consequence show “clear evidence of significant impact on spread and severity, and reduction of effectiveness of testing, treatment, and vaccination.”