Noncitizens in Multnomah County could be granted right to vote

Published 12:48 pm Tuesday, July 5, 2022

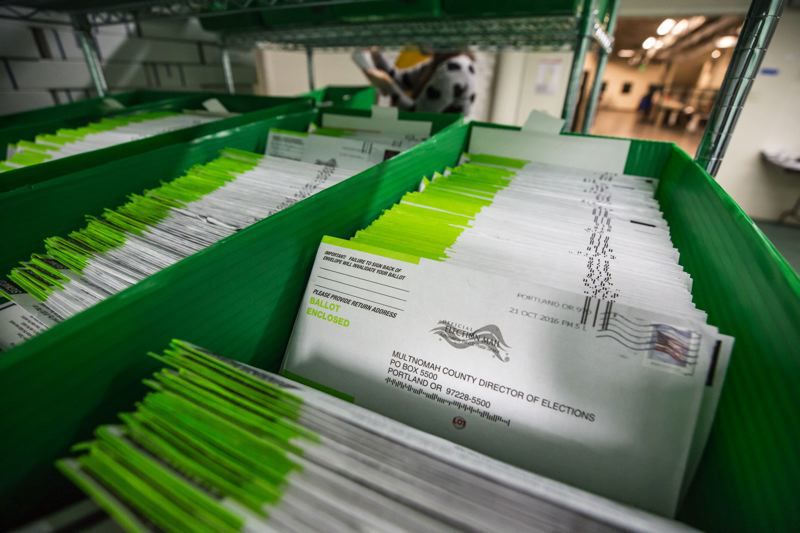

- PAMPLIN FILE PHOT - Ballots returned to the Multnomah County Clerk's Office

Voters in Multnomah County will see a ballot measure this November that would expand voting rights to residents who aren’t U.S. citizens.

Last month, a group tasked with reviewing Multnomah County’s charter — effectively a local constitution — unanimously recommended adding language that would extend voting rights to more groups, including people who are not citizens.

If voters pass the measure, Multnomah County would be the first jurisdiction in Oregon to grant the right to vote in local elections to “noncitizens.”

The county would be one of only a handful of jurisdictions in the United States that allow noncitizens to vote in local elections. Eleven cities in Maryland, two in Vermont and San Francisco currently allow voting by noncitizens.

The Multnomah County Charter Review Committee is expected to vote on specific charter language for the recommendation during its meeting Tuesday, July 5. The county convenes a charter review committee, comprising 16 appointed residents, every six years.

Expecting controversy, committee members chose broad language for the charter amendment to maximize who could gain voting rights as well as to avoid potential legal troubles.

“If we were to pursue one narrow declaration of who we would like to expand the vote to, if a court were to say, ‘No, you can’t do it that way,’ then there’s not as much recourse to really move this idea forward,” said Samantha Gladu, who helped draft the charter change and co-chairs the subcommittee that started discussions about it.

The language under consideration says the county shall extend the right to vote for county officers and measures “to the fullest extent allowed by law.”

At least one jurisdiction that tried to extend voting rights to noncitizens — New York City — saw the effort quashed by a court ruling. On June 27, a New York State Supreme Court justice struck down the measure approved by the city council last December, saying it violated the state’s constitution.

Noncitizens used to be able to vote

Juliet Stumpf, a professor at Lewis & Clark Law School who studies immigration and criminal law, was skeptical about the concept of noncitizen voting at first.

“I thought that (citizenship) was such a bedrock principle of our voting,” Stumpf said.

She had an open mind about it because, she said, everyone who has a stake in the community should have a voice in the political system.

It wasn’t until she and her students started researching the history of voting laws in Oregon and other states that she began to favor noncitizen voting.

Two of her students published an article in the Lewis & Clark Law Review last year that delves into the history of voting rights throughout the United States and makes a case for changing Oregon law statewide to allow voting by noncitizens.

Many states, including Oregon, allowed noncitizens to vote when they were founded. Racism and sexism were very explicit in the laws, Stumpf said.

Early Western states allowed noncitizens to vote as a way to encourage settling specifically by white European immigrants, the students found. In Oregon, white men who had resided in the state for six months prior to an election and declared an intent to become U.S. citizens could vote.

People have long applied measures of groups’ contributions to society as a means to decide whether they should be able to vote, Stumpf said. Literacy tests and proxies of taxation such as property ownership or residency were common qualifiers historically.

Charter review committee members cited multiple reasons for expanding voting rights, including reducing taxation without representation.

Undocumented people in Multnomah County pay an estimated $19 million in state and local taxes annually, according to a report by the Oregon Center for Public Policy. About half of those taxes are property taxes and the other half are income taxes and excise taxes on goods like gas and alcohol, the report shows.

Undocumented people aren’t eligible to access many of the social services to which they contribute, however. They can’t access Social Security, Medicare, the Oregon Health Plan after age 18, federal food assistance programs, and state and federal earned income tax credits, among others, the report states.

Oregonians voted overwhelmingly in favor — 80% — of eliminating noncitizen voting in 1914. The precise motivations are unclear, according to Stumpf’s students, because legislative records from that time don’t exist. But with the passage of a subsequent measure in 1916 that disenfranchised African, Asian and Native Americans in Oregon, the students concluded that racism and xenophobia were the only explanation. Xenophobia in the lead-up to World War I was apparent in other states’ reasons to eliminate noncitizen voting at the time, the students noted.

Realizing that citizenship as a prerequisite to voting “hadn’t been enshrined in the original constitution and that the change to barring noncitizens from voting had real racial and class-related foundations, I found that very troubling,” Stumpf said. “The advantages to noncitizen voting really stood out to me.”

Legal challenges

Granting voting rights to noncitizens likely will face substantial legal barriers, Katherine Thomas, assistant Multnomah County attorney, told committee members in March.

First, Oregon’s constitution requires citizenship for voting. State statutes related to voting refer to citizenship requirements, including one that says state voter registration cards must indicate a person is a U.S. citizen.

“Ultimately, it’s untested,” Thomas said. “I’m not aware that there is a local jurisdiction that has expanded voting to noncitizens. We don’t know how a court would necessarily treat that kind of proposal if it was challenged in court.”

The committee will present by Aug, 4 all of its recommended charter changes to the county board, which files the ballot title and other information with the elections division. Any ballot title challenges must be resolved by Sept. 8 to appear on the ballot for the Nov. 8 election.

If the measure passes, county staff would consult with the board about how to implement an expansion of voting rights, said Ryan Yambra, spokesperson for the county.

The committee also researched whether people under 18 and people currently prohibited from voting because they’re serving a sentence for a felony conviction could gain voting rights.

“The committee expects that the county will explore every possible avenue to expand local voting access,” Yambra said. “The details of implementation would depend on a variety of factors, and so we can’t say at this time whether or what board action might be required.”

Noncitizen residents include multiple groups, such as temporary residents with certain visas, permanent residents who hold green cards and undocumented immigrants.

Tens of thousands of people in Multnomah County could be granted the right to vote if the measure passes. Seven percent of the county’s population — or more than 56,000 people — is noncitizen residents, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2021 American Community Survey. An estimated 25,000 residents are undocumented, according to the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute.

The recommendation has received support from the Portland-based nonprofit Coalition of Communities of Color.

“The decisions of elected representatives impact every resident, regardless of whether they are eligible to vote,” Sol Mora, community engagement manager for the nonprofit, wrote in a letter to the committee. “This reform to expand our democracy will have a meaningful and lasting impact on communities across Multnomah County to feel that they belong and have a seat at the decision-making table.”